Warsaw Uprising

| Warsaw Uprising | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of "Operation Tempest", World War II | ||||||||

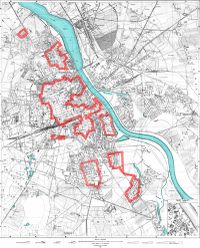

Polish Home Army positions, outlined in red, on day 4 (4 August 1944) |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski (P.O.W.) Antoni Chruściel (P.O.W.) Tadeusz Pełczyński Leopold Okulicki |

Walter Model Erich von dem Bach Rainer Stahel Heinz Reinefarth Bronislav Kaminski Petro Dyachenko |

Zygmunt Berling | ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| Range 20,000[4] to 49,000[5] (initially) | Range 13,000[6] to 25,000[7] (initially) | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Polish insurgents: 10,000 KIA[8] 5,200–6,000 MIA[8] 150,000–200,000 civilians killed,[9] 700,000 expelled from the city.[8] |

German forces: 2,000–3,000 KIA[8] 7,000 MIA[8] 9,000 WIA[8] 2,000 POW[8] 310 tanks and armored vehicles, 340 trucks and cars, 22 artillery pieces, one aircraft[8] |

Berling 1st Army: 5,660 casualties[8] | ||||||

|

|||||

The Warsaw Uprising (Polish: powstanie warszawskie) was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa), to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany, ahead of the Red Army advance. The rebellion coincided with retreat of German forces and Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city[10]. The Soviet advance stopped short, however, while Polish resistance against the German forces continued for 63 days until the Polish surrendered.

The Uprising began on 1 August 1944, as part of a nationwide rebellion, Operation Tempest, when the Soviet Army approached Warsaw. The main Polish objectives were to drive the German occupiers from the city and help with the larger fight against Germany and the Axis powers. Secondary political objectives were to liberate Warsaw before the Soviets, so as to underscore Polish sovereignty by empowering the Polish Underground State before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation could assume control.

Initially, the Poles seized substantial areas of the city, but the Soviets did not advance beyond the city's borders until mid-September. Inside the city, bitter fighting between the Germans and Poles continued. By 16 September, Soviet forces had reached a point a few hundred meters from the Polish positions, across the Vistula River, but they made no further headway during the Uprising, leading to allegations that the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had wanted the insurrection to fail so that the Soviet occupation of Poland would be uncontested.

Winston Churchill pleaded with Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt to help Britain's Polish allies, to no avail. Then, without Soviet air clearance, Churchill sent over 200 low-level supply-drops by the Royal Air Force, the South African Air Force and the Polish Air Force under British High Command. Later, after gaining Soviet air clearance, the USAAF sent one high-level mass airdrop as part of Operation Frantic.

Although the exact number of casualties remains unknown, it is estimated that about 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed and about 6,000 badly wounded. In addition, between 150,000 and 200,000 civilians died, mostly from mass murders conducted by troops fighting on the German side. German casualties totaled over 2,000 soldiers killed, 7,000 missing, and 9,000 wounded. During the urban combat approximately 25% of Warsaw's buildings were destroyed. Following the surrender of Polish forces, German troops systematically leveled 35% of the city block by block. Together with earlier damage suffered in the invasion of Poland (1939) and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1943), over 85% of the city was destroyed by January 1945, when the Soviets entered the city.

Contents |

Background

"We have one point from which every evil emanates. That point is Warsaw. If we didn't have Warsaw in the General Government, we wouldn't have four-fifths of the difficulties with which we must contend." - German Governor-General Hans Frank, Kraków, 14 December 1943[11]

By July 1944, Poland had been occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany for almost five years. The underground Polish Home Army, which was loyal to the Polish government-in-exile, had long planned some form of insurrection against the occupiers. Germany was fighting a coalition of Allied powers, led by the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union. The initial plan of the Home Army was to link up with the invading forces of the Western Allies as they liberated Europe from the Nazis. However, in 1943 it became apparent that the Soviets, rather than the Western Allies, would reach the pre-war borders of Poland before the Allied invasion of Europe made notable headway.[12] The Soviets and the Poles had a common enemy—Nazi Germany—but other than that, they were working towards different post-war goals; the Home Army desired a pro-Western, democratic Poland, but the Soviet leader Stalin intended to establish a communist, pro-Soviet regime. It became obvious that the advancing Soviet Red Army might not come to Poland as an ally but rather only as "the ally of an ally".[13]

The Soviets and the Poles distrusted each other, and Soviet partisans in Poland often clashed with Polish resistance increasingly united under the Home Army's front.[14] Stalin broke off Polish-Soviet relations on 25 April 1943 after the Germans revealed the Katyn massacre, but Stalin refused to admit it and blamed the Germans for propaganda. Afterwards, Stalin created the Rudenko-Commission, who's goal was to blame the Germans at all costs. The alliance took Stalin's words as truth to keep the Anti-Nazi alliance.[15] On 26 October, the Polish government-in-exile issued an instruction to the effect that if diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union were not resumed before the Soviet entry into Poland, Home Army forces were to remain underground pending further decisions. However, the Home Army commander, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, took a different approach, and on 20 November, he outlined his own plan, which became known as "Operation Tempest". On the approach of the Eastern Front, local units of the Home Army were to harass the German Wehrmacht in the rear and co-operate with incoming Soviet units as much as possible. Although doubts existed about the military wisdom of a major uprising, planning continued.[16]

Eve of the battle

The situation came to a head on 13 July 1944 as the Soviet offensive crossed the old Polish border. At this point the Poles had to make a decision: either initiate the uprising in the current difficult political situation and risk problems with Soviet support, or fail to rebel and face Soviet propaganda describing the Home Army as impotent or worse, Nazi collaborators. They feared that if Poland was 'liberated' by the Red Army, then the Allies would ignore the London-based Polish government in the aftermath of the war. The urgency for a final decision on strategy increased as it became clear that after successful Polish-Soviet co-operation in the liberation of Polish territory (for example, in Operation Ostra Brama), Soviet security forces behind the frontline shot or arrested Polish officers and forcibly conscripted lower ranks into the Soviet-controlled forces.[14][17] On 21 July, the High Command of the Home Army decided that the time to launch Operation Tempest in Warsaw was imminent.[18] The plan was intended both as a political manifestation of Polish sovereignty and as a direct operation against the German occupiers.[8] On 25 July, the Polish government-in-exile (without the knowledge and against the wishes of Polish Commander-in-Chief General Kazimierz Sosnkowski[19]) approved the plan for an uprising in Warsaw with the timing to be decided locally.[20]

In the early summer of 1944, German plans required Warsaw to serve as the defensive center of the area and to be held at all costs. The Germans had fortifications constructed and built up their forces in the area. This process slowed after the failed 20 July Plot to assassinate the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, and around that time, the Germans in Warsaw were weak and visibly demoralized.[21][22] However, by the end of July, German forces in the area were reinforced.[21] On 27 July, the Governor of the Warsaw District, Ludwig Fischer, called for 100,000 Polish men and women to report for work as part of a plan which envisaged the Poles constructing fortifications around the city.[23] The inhabitants of Warsaw ignored his demand, and the Home Army command became worried about possible reprisals or mass round-ups, which would disable their ability to mobilize.[24] The Soviet forces were approaching Warsaw, and Soviet-controlled radio stations called for the Polish people to rise in arms.[21][25] On 25 July, the Union of Polish Patriots, in a broadcast from Moscow, stated: "The Polish Army of Polish Patriots... calls on the thousands of brothers thirsting to fight, to smash the foe before he can recover from his defeat... Every Polish homestead must become a stronghold in the struggle against the invaders... Not a moment is to be lost."[26] On 29 July, the first Soviet armored units reached the outskirts of Warsaw, where they were counter-attacked by two German Panzer Corps: the 39th and 4th SS.[27] On 29 July 1944 Radio Station Kosciuszko located in Moskow emitted few times His "Appeal to Warsaw" and called to "Fight The Germans!": "No doubt Warsaw already hears the guns of the battle which is soon to bring her liberation. [...] The Polish Army now entering Polish territory, trained in the Soviet Union, is now joined to the People's Army to form the Corps of the Polish Armed Forces, the armed arm of our nation in its struggle for independence. Its ranks will be joined tomorrow by the sons of Warsaw. They will all together, with the Allied Army pursue the enemy westwards, wipe out the Hitlerite vermin from Polish land and strike a mortal blow at the beast of Prussian Imperialism." [28][29] Bór-Komorowski and several high-ranking officers held a meeting on that day. Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, who had recently arrived from London, expressed the view that support from the Allies would be weak, but his points received little attention.[30] Believing that the time for action had arrived, on 31 July, the Polish commanders General Bór-Komorowski and Colonel Antoni Chruściel ordered full mobilization of Home Army forces for 17:00 the following day.[31]

Opposing forces

Poles

|

Polish forces areas

|

Within the framework of the entire enemy intelligence operations directed against Germany, the intelligence service of the Polish resistance movement assumed major significance. The scope and importance of the operations of the Polish resistance movement, which was ramified down to the smallest splinter group and brilliantly organized, have been in (various sources) disclosed in connection with carrying out of major police security operations.

The Home Army forces of the Warsaw District numbered between 20,000[4][32] and 49,000[5] soldiers. Other formations also contributed soldiers; estimates range from 2,000 in total[33] to about 3,500 from the far-right National Armed Forces and a few dozen from the communist People's Army.[34] Most of them had trained for several years in partisan and urban guerrilla warfare, but lacked experience in prolonged daylight fighting. The forces lacked equipment,[7] because the Home Army had shuttled weapons to the east of the country before the decision to include Warsaw in Operation Tempest.[35] Other partisan groups subordinated themselves to Home Army command, and many volunteers joined during the fighting, including Jews freed from the Gęsiówka concentration camp in the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto.[36]

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (codename "Monter") commanded the Polish forces in Warsaw. Initially he divided his forces into eight areas.[37] On 20 September, they were reorganized to align with the three areas of the city held by Polish forces. The entire force, renamed the Warsaw Home Army Corps (Polish: Warszawski Korpus Armii Krajowej) and commanded by General Antoni Chruściel—promoted from Colonel on 14 September—formed into three infantry divisions (Śródmieście, Żoliborz and Mokotów).[37]

|

Polish military supplies

As of 1 August their military supplies consisted of:

|

During the fighting, the Poles obtained additional supplies through airdrops and by capture from the enemy (including several armoured vehicles, most notably two Panther tanks and two SdKfz.251 APCs).[39][40][41] Also, the insurgents' workshops produced weapons throughout the fighting, including submachine guns, K pattern flamethrowers,[42] grenades, mortars, and even an armoured car (Kubuś).[43]

Germans

In late July 1944 the German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories. The first and the most numerous was the garrison of Warsaw. As of 31 July, it numbered some 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.[44]

|

German forces

These forces included:

|

These well-equipped German forces prepared for the defence of the city's key positions for many months. Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines protected the buildings and areas occupied by the Germans. Apart from the garrison itself, numerous army units were stationed on both banks of the Vistula and in the city. The second category was formed by police and SS under Col. Paul Otto Geibel, numbering initially 5,710 men,[45] including Schutzpolizei and Waffen-SS.[46] The third category was formed by various auxiliary units, including detachments of the Bahnschutz (rail guard), Werkschutz (factory guard), Sonderdienst and Sonderabteilungen (military Nazi party units).[47]

During the uprising the German side received reinforcements on a daily basis, and Stahel was replaced as overall commander by SS-General Erich von dem Bach in early August. As of 20 August 1944, the German units directly involved with fighting in Warsaw comprised 17,000 men arranged in two battle groups:[48] Battle Group Rohr (commanded by Major General Rohr), which included Bronislav Kaminski's brigade and Battle Group Reinefarth (commanded by SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth) consisted of Attack Group Dirlewanger (commanded by Oskar Dirlewanger), Attack Group Reck (commanded by Major Reck), Attack Group Schmidt (commanded by Colonel Schmidt) and various support and backup units.

Uprising

W-hour

After days of hesitation, at 17:00 on 31 July, the Polish headquarters scheduled "W-hour" (from the Polish wybuch, "explosion"; also wolność, freedom), the moment of the start of the uprising, for 17:00 on the following day.[49] The decision proved to be a costly strategic mistake because the under-equipped Polish forces were prepared for a series of coordinated surprise night attacks. Attacking during daylight exposed them to German machine gun fire. Although many partisan units were already mobilized and waiting at assembly points throughout the city, the mobilization of thousands of young men and women was hard to conceal. Sporadic fighting started in advance of "W-hour", notably in Żoliborz,[50] and around Napoleon Square and Dąbrowski Square.[51] The Germans had anticipated the possibility of an uprising, though they had not realised its size or strength.[52] At 16:30 Governor Fischer put the garrison on full alert.[53]

That evening the insurgents captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station, Praga railway station and the tallest building in Warsaw, the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport remained in German hands.[54] The first two days were crucial in establishing the battlefield for the rest of the fight. The insurgents were most successful in the City Center, Old Town, and Wola districts. However, several major German strongholds remained, and in some areas of Wola the Poles sustained heavy losses that forced an early retreat. In other areas such as Mokotów, the attackers almost completely failed to secure any objectives and controlled only the residential areas. In Praga, on the east bank of the Vistula, the Poles were sent back into hiding by a high concentration of German forces.[55] Most crucially, the fighters in different areas failed to link up, either with each other or with areas outside Warsaw, leaving each sector isolated from the others. After the first hours of fighting, many units adopted a more defensive strategy, while civilians began erecting barricades. Despite all the problems, by 4 August most of the city was in Polish hands.

First four days

.jpg)

The uprising was intended to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived;[56] however, this never happened, and the Polish forces had to fight with little outside assistance. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were as follows:

- Area I (city center and the Old Town): Units captured most of their assigned territory, but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of resistance from the Germans (the Warsaw University buildings, PAST skyscraper, the headquarters of the German garrison in the Saxon Palace, the German-only area near Szucha Avenue, and the bridges over the Vistula). They thus failed to create a central stronghold, secure communication links to other areas, or a secure land connection with the northern area of Żoliborz through the northern railway line and the Citadel.

- Area II (Żoliborz, Marymont, Bielany): Units failed to secure the most important military targets near Żoliborz. Many units retreated outside of the city, into the forests. Although they captured most of the area around Żoliborz, the soldiers of Colonel Mieczysław Niedzielski ("Żywiciel") failed to secure the Citadel area and break through German defences at Warsaw Gdańsk railway station.[57]

- Area III (Wola): Units initially secured most of the territory, but sustained heavy losses (up to 30%). Some units retreated into the forests, while others retreated to the eastern part of the area. In the northern part of Wola the soldiers of Colonel Jan Mazurkiewicz ("Radosław") managed to capture the German barracks, the German supply depot at Stawki Street, and the flanking position at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery.

- Area IV (Ochota): The units mobilized in this area did not capture either the territory or the military targets (the Gęsiówka concentration camp, and the SS and Sipo barracks on Narutowicz Square). After suffering heavy casualties most of the Home Army forces retreated to the forests west of Warsaw. Only two small units of approximately 200 to 300 men under Lieut. Andrzej Chyczewski ("Gustaw") remained in the area and managed to create strong pockets of resistance. They were later reinforced by units from the city center. Elite units of the Kedyw managed to secure most of the northern part of the area and captured all of the military targets there. However, they were soon tied down by German tactical counter-attacks from the south and west.

- Area V (Mokotów): The situation in this area was very serious from the start of hostilities. The partisans aimed to capture the heavily defended Police Area (Dzielnica policyjna) on Rakowiecka Street, and establish a connection with the city center through open terrain at the former airfield of Pole Mokotowskie. As both of the areas were heavily fortified and could be approached only through open terrain, the assaults failed. Some units retreated into the forests, while others managed to capture parts of Dolny Mokotów, which was, however, severed from most communication routes to other areas.[58] The last building held was on the corner of the Avenue of Independence and Rakowieczka Street under formidable assault by German Panzers. This building was named by Second Lieutenant Andrzej Zwartynski - "Zyndram" - of Compania 02, "Baszta" saying, "This is our Alcazar", in reference to the Siege of the Alcázar in which the nationalist forces held the castle Alcázar of Toledo against overwhelming Spanish Republican forces, in the Spanish Civil war.

- Area VI (Praga): The Uprising was also started on the right bank of the Vistula, where the main task was to seize the bridges on the river and secure the bridgeheads until the arrival of the Red Army. It was clear that, since the location was far worse than that of the other areas, there was no chance of any help from outside. After some minor initial successes, the forces of Lt.Col. Antoni Żurowski ("Andrzej") were badly outnumbered by the Germans. The fights were halted, and the Home Army forces were forced back underground.[49]

- Area VII (Powiat warszawski): this area consisted of territories outside Warsaw city limits. Actions here mostly failed to capture their targets.

An additional area within the Polish command structure was formed by the units of the Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion or Kedyw, an elite formation that was to guard the headquarters and was to be used as an "armed ambulance", thrown into the battle in the most endangered areas. These units secured parts of Śródmieście and Wola; along with the units of Area I, they were the most successful during the first few hours.

Among the most notable primary targets that were not taken during the opening stages of the uprising were the airfields of Okęcie and Pole Mokotowskie, as well as the PAST skyscraper overlooking the city center and the Gdańsk railway station guarding the passage between the center and the northern borough of Żoliborz.

Wola massacre

The Uprising reached its apogee on 4 August when the Home Army soldiers managed to establish front lines in the westernmost boroughs of Wola and Ochota. However, it was also the moment at which the German army stopped its retreat westwards and began receiving reinforcements. On the same day SS General Erich von dem Bach was appointed commander of all the forces employed against the Uprising.[49] German counter-attacks aimed to link up with the remaining German pockets and then cut off the Uprising from the Vistula river. Among the reinforcing units were forces under the command of Heinz Reinefarth.[49]

On 5 August Reinefarth's three attack groups started their advance westward along Wolska and Górczewska streets toward the main East-West communication line of Jerusalem Avenue. Their advance was halted, but the regiments began carrying out Heinrich Himmler's orders: behind the lines, special SS, police and Wehrmacht groups went from house to house, shooting the inhabitants regardless of age or gender and burning their bodies.[49] Estimates of civilians killed in Wola and Ochota range from 20,000 to 50,000,[59] 40,000 by 8 August in Wola alone,[60] or as high as 100,000.[61] The main perpetrators were Oskar Dirlewanger and Bronislav Kaminski, who committed the cruelest atrocities.[62][63][64]

The policy was designed to crush the Poles' will to fight and put the uprising to an end without having to commit to heavy city fighting.[65] With time, the Germans realized that atrocities only stiffened resistance and that some political solution should be found, as the thousands of men at the disposal of the German commander were unable to effectively counter the insurgents in an urban guerilla setting.[66] They aimed to gain a significant victory to show the Home Army the futility of further fighting and induce them to surrender. This did not succeed. Until mid-September, the Germans shot all captured insurgents on the spot, but from the end of September, some of the captured Polish soldiers were treated as POWs.[67]

Stalemate

"This is the fiercest of our battles since the start of the war. It compares to the street battles of Stalingrad." - SS chief Heinrich Himmler to other German generals on 21 September 1944.[68]

Despite the loss of Wola, the Polish resistance stiffened. Zośka and Wacek battalions managed to capture the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto and liberate the Gęsiówka concentration camp, freeing about 350 Jews.[49] The area became one of the main communication links between the insurgents fighting in Wola and those defending the Old Town. On 7 August German forces were strengthened by the arrival of tanks using civilians as human shields.[49] After two days of heavy fighting they managed to bisect Wola and reach Bankowy Square. However, by then the net of barricades, street fortifications and tank obstacles was already well-prepared and both sides reached a stalemate, with heavy house-to-house fighting.

Between 9 August and 18 August pitched battles raged around the Old Town and nearby Bankowy Square, with successful attacks by the Germans and counter-attacks from the Poles. German tactics hinged on bombardment through the use of heavy artillery[69] and tactical bombers, against which the Poles were unable to effectively defend, as they lacked anti-aircraft artillery weapons. Even clearly marked hospitals were dive-bombed by Stukas.[70]

Although the Battle of Stalingrad had already shown the danger a city can pose to armies which fight within it and the importance of local support, the Warsaw Uprising was probably the first demonstration that in an urban terrain, a vastly under-equipped force supported by the civilian population can hold its own against better-equipped professional soldiers—though at the cost of considerable sacrifice on the part of the city's residents. The Poles held the Old Town until a decision to withdraw was made at the end of August. On successive nights until 2 September, the defenders of the Old Town withdrew through the sewers, which were a major means of communication between different parts of the Uprising.[71] Thousands of people were evacuated in this way. Those that remained were either shot or transported to concentration camps like Mauthausen and Sachsenhausen once the Germans regained control.[72]

Berling's landings

Soviet attacks on the 4th SS Panzer Corps east of Warsaw were renewed on 26 August, and the Germans were forced to retreat into Praga. The Soviet army under the command of Konstantin Rokossovsky captured Praga and arrived on the east bank of the Vistula in mid-September. By 13 September, the Germans had destroyed the remaining bridges over the Vistula, signalling that they were abandoning all their positions east of the river.[73] In the Praga area Polish units under the command of General Zygmunt Berling (thus sometimes known as berlingowcy – "the Berling men") fought on the Soviet side. Three patrols of his 1st Polish Army (Polish: 1 Armia Wojska Polskiego) landed in the Czerniaków and Powiśle areas and made contact with Home Army forces on the night of 14/15 September. The artillery cover and air support provided by the Soviets was unable to effectively counter enemy machine-gun fire as the Poles crossed the river, and the landing troops sustained heavy losses.[74] Only small elements of the main units made it ashore (I and III battalions of 9th infantry regiment, 3rd Infantry Division).[75]

The limited landings by the 1st Polish Army represented the only external ground force which arrived to physically support the uprising; and even they were curtailed by the Soviet High Command.[75]

The Germans intensified their attacks on the Home Army positions near the river to prevent any further landings, but were not able to make any significant advances for several days while Polish forces held those vital positions in preparation for a new expected wave of Soviet landings. Polish units from the eastern shore attempted several more landings, and from 15 to 23 September sustained heavy losses (including the destruction of all their landing boats and most of their other river crossing equipment).[75] Red Army support was inadequate.[75] After the failure of repeated attempts by the 1st Polish Army to link up with the insurgents, the Soviets limited their assistance to sporadic artillery and air support. Conditions that prevented the Germans from dislodging the insurgents also acted to prevent the Poles from dislodging the Germans. Plans for a river crossing were suspended "for at least 4 months", since operations against the 9th Army's five panzer divisions were problematic at that point, and the commander of the 1st Polish Army, General Berling was relieved of his duties by his Soviet superiors.[14][76] On the night of 19 September, after no further attempts from the other side of the river were made and the promised evacuation of wounded did not take place, Home Army soldiers and landed elements of the 1st Polish Army were forced to begin a retreat from their positions on the bank of the river.[75] Out of approximately 900 men who made it ashore only a handful made it back to the eastern shore of the Vistula.[77] Berling's Polish Army losses in the attempt to aid the Uprising were 5,660 killed, missing or wounded.[8]

From this point on, the Warsaw Uprising can be seen as a one-sided war of attrition or, alternatively, as a fight for acceptable terms of surrender. The Poles were besieged in three areas of the city: Śródmieście, Żoliborz and Mokotów.

Life behind the lines

In 1939 Warsaw had roughly 1,350,000 inhabitants. Over a million were still living in the city at the start of the Uprising. In Polish-controlled territory, during the first weeks of the Uprising, people tried to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country. Cultural life was vibrant, both among the soldiers and civilian population, with theatres, post offices, newspapers and similar activities.[78] Boys and girls of the Polish Scouts acted as couriers for an underground postal service, risking their lives daily to transmit any information that might help their people.[49][79] Near the end of the Uprising, lack of food, medicine, overcrowding and indiscriminate German air and artillery assault on the city made the civilian situation more and more desperate.

Food shortages

As the Uprising was supposed to be relieved by the Soviets in a matter of days, the Polish underground did not predict food shortages would be a problem. However, as the fighting dragged on, the inhabitants of the city faced hunger and starvation. A major break-through took place on 6 August, when Polish units recaptured the Haberbusch i Schiele brewery complex at Ceglana Street. From that time on the Varsovians lived mostly on barley from the brewery's warehouses. Every day up to several thousand people organized into cargo teams reported to the brewery for bags of barley and then distributed them in the city center. The barley was then ground in coffee grinders and boiled with water to form a so-called spit-soup (Polish: pluj-zupa). The "Sowiński" Battalion managed to hold the brewery until the end of the fighting.

Another serious problem for civilians and soldiers alike was a shortage of water.[49] By mid-August most of the water conduits were either out of order or filled with corpses. In addition, the main water pumping station remained in German hands.[49] To prevent the spread of epidemics and provide the people with water, the authorities ordered all janitors to supervise the construction of water wells in the backyards of every house. On 21 September the Germans blew up the remaining pumping stations at Koszykowa Street and after that the public wells were the only source of potable water in the besieged city.[80] By the end of September, the city center had more than 90 functioning wells.[49]

Polish media

Before the Uprising the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Home Army had set up a group of war correspondents. Headed by Antoni Bohdziewicz, the group made three newsreels and over 30,000 meters of film tape documenting the struggles. The first newsreel was shown to the public on 13 August in the Palladium cinema at Złota Street.[49] In addition to films, dozens of newspapers appeared from the very first days of the uprising. Several previously underground newspapers started to be distributed openly.[81][82] The two main daily newspapers were the government-run Rzeczpospolita Polska and military Biuletyn Informacyjny. There were also several dozen newspapers, magazines, bulletins and weeklies published routinely by various organizations and military units.[81]

The Błyskawica long-range radio transmitter, assembled on 7 August in the city center, was run by the military, but was also used by the recreated Polish Radio from 9 August.[49] It was on the air three or four times a day, broadcasting news programmes and appeals for help in Polish, English, German and French, as well as reports from the government, patriotic poems and music.[83] It was the only such radio station in German-held Europe.[84] Among the speakers appearing on the insurgent radio were Jan Nowak-Jeziorański,[85] Zbigniew Świętochowski, Stefan Sojecki, Jeremi Przybora,[86] and John Ward, a war correspondent for The Times of London.[87]

Lack of outside support

According to many historians, a major cause of the eventual failure of the uprising was the almost complete lack of outside support and the late arrival of that which did arrive.[8][27] The Polish government-in-exile carried out frantic diplomatic efforts to gain support from the Western Allies prior to the start of battle but the allies would not act without Soviet approval. The Polish government in London asked the British several times to send an allied mission to Poland;[14] since such missions had already been dispatched to other resistance movements in Europe. However, the British mission did not arrive until December 1944.[88] Shortly after their arrival, they met up with Soviet authorities, who arrested and imprisoned them.[89] In the words of the mission's deputy commander, it was "a complete failure".[90] Nevertheless, from August 1943 to July 1944, over 200 Royal Air Force (RAF) flights dropped an estimated 146 Polish personnel trained in Great Britain, over 4000 containers of supplies, and $16 million in banknotes and gold to the Home Army.[91]

The only support operation which ran continuously for the duration of the Uprising were night supply drops by long-range planes of the RAF, other British Commonwealth air forces, and units of the Polish Air Force, which had to use distant airfields in Italy, reducing the amount of supplies they could carry. The RAF made 223 sorties and lost 34 aircraft. The effect of these airdrops was mostly psychological—they delivered too few supplies for the needs of the insurgents, and many airdrops landed outside insurgent-controlled territory.

Airdrops

"There was no difficulty in finding Warsaw. It was visible from 100 kilometers away. The city was in flames and with so many huge fires burning, it was almost impossible to pick up the target marker flares." - William Fairly, a South African pilot, from an interview in 1982[92]

From 4 August the Western Allies began supporting the Uprising with airdrops of munitions and other supplies.[93] Initially the flights were carried out mostly by the 1568th Polish Special Duties Flight of the Polish Air Force stationed in Bari and Brindisi in Italy, flying B-24 Liberator, Handley Page Halifax and Douglas C-47 Dakota planes. Later on, at the insistence of the Polish government-in-exile, they were joined by the Liberators of 2 Wing –No. 31 and No. 34 Squadrons of the South African Air Force based at Foggia in Southern Italy, and Halifaxes, flown by No. 148 and No. 178 RAF Squadrons. The drops by British, Polish and South African forces continued until 21 September. The total weight of allied drops varies according to source (104 tons,[94] 230 tons[93] or 239 tons[14]), over 200 flights were made.[95]

The Soviet Union did not allow the Western Allies to use its airports for the airdrops,[8] so the planes had to use bases in the United Kingdom and Italy which reduced their carrying weight and number of sorties. The Allies' specific request for the use of landing strips made on 20 August was denied by Stalin on 22 August.[92] Stalin referred to the insurgents as "a handful of criminals"[96] and stated that the uprising was inspired by "enemies of the Soviet Union".[97]) Thus by denying landing rights to Allied aircraft on Soviet-controlled territory the Soviets vastly limited effectiveness of Allied assistance to the Uprising, and even fired at Allied airplanes which carried supplies from Italy and strayed into Soviet-controlled airspace.[92]

American support was also limited. After Stalin's objections to supporting the uprising, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill telegraphed U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 25 August and proposed sending planes in defiance of Stalin, to "see what happens". Unwilling to upset Stalin before the Yalta Conference, Roosevelt replied on 26 August: "I do not consider it advantageous to the long-range general war prospect for me to join you".[92][98]

.jpg)

Finally on 18 September the Soviets allowed a USAAF flight of 107 B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 3 division Eighth Air Force to re-fuel and reload at Soviet airfields used in Operation Frantic, but it was too little too late. The planes dropped 100 tons of supplies but only 20 were recovered by the insurgents due to the wide area over which they were spread.[97] The vast majority of supplies fell into German-held areas.[99] The USAAF lost two B-17s[100] with a further seven damaged. The planes landed at the Operation Frantic airbases in the Soviet Union. There they were rearmed and refuelled and the next day 100 B-17s and 61 P-51s left the USSR to bomb the marshalling yard at Szolnok in Hungary on their way back to bases in Italy.[101] Soviet intelligence reports show that Soviet commanders on the ground near Warsaw estimated that 96% of the supplies dropped by the Americans fell into German hands.[102] From the Soviet perspective, the Americans were supplying the Nazis instead of aiding the insurgents.[103] The Soviets refused permission for any further American flights until 30 September, by which time the weather was too poor to fly, and the insurgency was nearly over.[104]

From 14 September the Soviets began their own airdrops, dropping about 55 tons in total until 28 September. However, since the Soviet airmen did not equip the containers with parachutes, many of the packages were damaged.[105]

Although German air defence over the Warsaw area itself was almost non-existent, about 12% of the 296 planes taking part in the operations were lost because they had to fly 1,600 km out and the same distance back over heavily defended enemy territory (112 out of 637 Polish and 133 out of 735 British and South African airman were shot down).[97] Most of the drops were made during night, at no more than 100–300 feet altitude, and poor accuracy left many parachuted packages stranded behind German-controlled territory (only about 50 tons of supplies, less than 50% delivered, was recovered by the insurgents).[93]

Soviet stance

"Fight The Germans! No doubt Warsaw already hears the guns of the battle which is soon to bring her liberation. ... The Polish Army now entering Polish territory, trained in the Soviet Union, is now joined to the People's Army to form the Corps of the Polish Armed Forces, the armed arm of our nation in its struggle for independence. Its ranks will be joined tomorrow by the sons of Warsaw. They will all together, with the Allied Army pursue the enemy westwards, wipe out the Hitlerite vermin from Polish land and strike a mortal blow at the beast of Prussian Imperialism." - Moscow Radio Station Kosciuszko, 29 July 1944 broadcast[28]

The role of the Red Army during the Warsaw Uprising remains controversial and is still disputed by historians.[27] The Uprising started when the Red Army appeared on the city's doorstep, and the Poles in Warsaw were counting on Soviet aid coming in a matter of days. This basic scenario of an uprising against the Germans launched a few days before the arrival of Allied forces played out successfully in a number of European capitals, notably Paris[106] and Prague. However, despite retaining positions south-east of Warsaw barely 10 km from the city center for about 40 days, the Soviets did not extend effective aid to the desperate city. The sector was held by the understrength German 73rd Infantry Division, destroyed many times on the Eastern Front and recently reconstituted.[107] The division, though weak, did not experience significant Soviet pressure during that period. The Red Army was fighting intense battles to the south of Warsaw, to seize and maintain bridgeheads over the Vistula river, and to the north, to gain bridgeheads over the river Narew. The best German armored divisions were fighting on those sectors. Despite that, both of these objectives had been mostly secured by early September. The Soviet 47th army did not move into Praga, on the right bank of the Vistula, until the 11th of September. In three days the Soviets gained control of the suburb, a few hundred meters from the main battle on the other side of the river, as the resistance by the German 73rd division collapsed quickly. If the Soviets had reached this stage in early August, the crossing of the river would have been easier, as the Poles then held considerable stretches of the riverfront. However, by mid-September a series of German attacks had reduced the Poles to holding one narrow stretch of the riverbank, in the district of Czerniaków. The Poles were counting on the Soviet forces to cross to the left bank where the main battle of the uprising was occurring. Though Berling's 1st Polish army did cross the river, their support from the Soviets was inadequate and the main Soviet force did not follow them.[108]

One of the reasons given for the failure of the uprising was the reluctance of the Soviet Red Army to help the Resistance. On 1 August, only several hours prior to the outbreak of the uprising, the Soviet advance was halted by a direct order from the Kremlin.[109] Soon afterwards the Soviet tank units stopped receiving any oil from their depots.[109] By then the Soviets knew of the planned outbreak from their agents in Warsaw and, more importantly, from the Polish prime minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk, who informed them of the Polish plans a few hours before.[109][110] The Red Army's halt and lack of support for the Polish resistance is seen as a calculated decision by Stalin to achieve certain post-war political objectives.[14] Had the Home Army triumphed, the Polish government-in-exile would have increased its political and moral legitimacy to reinstate a government of its own, rather than accept a Soviet regime. The destruction of the Polish resistance by the Nazis was of long-term benefit to Stalin; it weakened future Polish opposition to Soviet occupation, and enabled the Soviets to say they "liberated" Warsaw.[14]

One way or the other, the presence of Soviet tanks in nearby Wołomin 15 kilometers to the east of Warsaw had sealed the decision of the Home Army leaders to launch the uprising. However, as a result of the initial battle of Radzymin in the final days of July, these advance units of the Soviet 2nd Tank Army were pushed out of Wołomin and back about 10 km.[111][112][113] On 9 August, Stalin informed Premier Mikołajczyk that the Soviets had originally planned to be in Warsaw by 6 August, but a counter-attack by four Panzer divisions had thwarted their attempts to reach the city.[114] By 10 August, the Germans had enveloped and inflicted heavy casualties on the Soviet 2nd Tank Army at Wołomin.[27] When Stalin and Churchill met face-to-face in October 1944, Stalin told Churchill that the lack of Soviet support was a direct result of a major reverse in the Vistula sector in August, which had to be kept secret for strategic reasons.[115] All contemporary German sources assumed that the Soviets were trying to link up with the insurgents, and they believed it was their defense that prevented the Soviet advance rather than a reluctance to advance on the part of the Soviets.[116] Nevertheless, as part of their strategy the Germans published propaganda accusing both the British and Soviets of abandoning the Poles.[117]

The Soviet units which reached the outskirts of Warsaw in the final days of July 1944 had advanced from the 1st Belorussian Front in Western Ukraine as part of the Lublin-Brest Offensive Operation, between the Lvov-Sandomierz Operation on its left and Operation Bagration on its right.[27] These two flanking operations were colossal defeats for the German army and completely destroyed a large number of German formations.[27] As a consequence, the Germans at this time were desperately trying to put together a new force to hold the line of the Vistula, the last major river barrier between the Red Army and Germany proper, rushing in units in various stages of readiness from all over Europe. These included many infantry units of poor quality,[118] and 4–5 high quality Panzer Divisions in the 39th Panzer Corps and 4th SS Panzer Corps[27] pulled from their refits.[118]

Other possible explanations for Soviet conduct are possible. The Red Army geared for a major thrust into the Balkans through Romania in mid-August and a large proportion of Soviet resources was sent in that direction, while the offensive in Poland was put on hold.[119] Stalin had made a strategic decision to concentrate on occupying Eastern Europe, rather than on making a thrust toward Germany.[120] The capture of Warsaw was not essential for the Soviets, as they had already seized a series of convenient bridgeheads to the south of Warsaw, and were concentrating on defending them against vigorous German counterattacks.[27] Finally, the Soviet High Command may not have developed a coherent or appropriate strategy with regard to Warsaw because they were badly misinformed.[121] Propaganda from the Polish Committee of National Liberation minimized the strength of the Home Army and portrayed them as Nazi sympathizers.[122] Information submitted to Stalin by intelligence operatives or gathered from the frontline was often inaccurate or omitted key details.[123] Possibly because the operatives were unable, due to the harsh political climate, to express opinions or report facts honestly, so they "deliberately resorted to writing nonsense".[124]

According to David Glantz, the Red Army was simply unable to extend effective support to the uprising, which began too early, regardless of Stalin's political intentions.[27] German military capabilities in August—early September were sufficient to halt any Soviet assistance to the Poles in Warsaw, were it intended.[27] In addition, Glantz argued that Warsaw would be a costly city to clear it of Germans and an unsuitable location as a start point for subsequent Red Army offensives.[27]

Aftermath

Capitulation

The 9th Army has crushed the final resistance in the southern Vistula circle. The insurgents fought to the very last bullet.

By the first week of September both German and Polish commanders realized that the Soviet army was unlikely to act to break the stalemate. The Germans reasoned that a prolonged insurgency would damage their ability to hold Warsaw as the frontline; the Poles were concerned that continued resistance would result in further massive casualties. On 7 September, General Rohr proposed negotiations, which Bór-Komorowski agreed to pursue the following day.[125] Over the 8, 9 and 10 September about 20,000 civilians were evacuated by agreement of both sides, and Rohr recognized the right of Home Army insurgents to be treated as combatants.[126] The Poles suspended talks on the 11th, as they received news that the Soviets were advancing slowly through Praga.[127] A few days later, the arrival of the 1st Polish army breathed new life into the resistance and the talks collapsed.[128]

However, by the morning of 27 September, the Germans had retaken Mokotów.[129] Talks restarted on 28 September.[130] In the evening of 30 September, Żoliborz fell to the Germans.[131] The Poles were being pushed back into fewer and fewer streets, and their situation was ever more desperate.[132] On the 30th, Hitler decorated von dem Bach, Dirlewanger and Reinefarth, while in London General Sosnkowski was dismissed as Polish commander-in-chief. Bór-Komorowski was promoted in his place, even though he was trapped in Warsaw.[133] Bór-Komorowski and Prime Minister Mikołajczyk again appealed directly to Rokossovky and Stalin for a Soviet intervention.[134] None came. According to Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who was by this time at the Vistula front, both he and Rokossovsky advised Stalin against an offensive because of heavy Soviet losses.[135]

The capitulation order of the remaining Polish forces was finally signed on 2 October. All fighting ceased that evening.[49][136] According to the agreement, the Wehrmacht promised to treat Home Army soldiers in accordance with the Geneva Convention, and to treat the civilian population humanely.[49]

The next day the Germans began to disarm the Home Army soldiers. They later sent 15,000 of them to POW camps in various parts of Germany. Between 5,000 and 6,000 insurgents decided to blend into the civilian population hoping to continue the fight later. The entire civilian population of Warsaw was expelled from the city and sent to a transit camp Durchgangslager 121 in Pruszków.[137] Out of 350,000–550,000 civilians who passed through the camp, 90,000 were sent to labour camps in the Third Reich, 60,000 were shipped to death and concentration camps (including Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen, among others), while the rest were transported to various locations in the General Government and released.[137]

The Eastern Front remained static in the Vistula sector, with the Soviets making no attempt to push forward, until the Vistula-Oder Offensive began on 12 January 1945. Almost entirely destroyed, Warsaw was liberated from the Germans on 17 January 1945 by the Red Army and the 1st Polish Army.[49]

Destruction of the city

"The city must completely disappear from the surface of the earth and serve only as a transport station for the Wehrmacht. No stone can remain standing. Every building must be razed to its foundation." - SS chief Heinrich Himmler, 17 October, SS officers conference[68]

The destruction of the Polish capital was planned before the start of World War II. On 20 June 1939 while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in Würzburg am Main, his attention was captured by a project of a future German town – "Neue deutsche Stadt Warschau". According to the Pabst Plan Warsaw was to be turned into a provincial German city. It was soon included as a part of the great germanization plan of the East; the genocidal Generalplan Ost. The failure of the Warsaw Uprising provided an opportunity for Hitler to begin the transformation.[138]

After the remaining population had been expelled, the Germans continued the destruction of the city.[8] Special groups of German engineers were dispatched to burn and demolish the remaining buildings. According to German plans, after the war Warsaw was to be turned into nothing more than a military transit station,[68] or even a lake.[139] The demolition squads used flame-throwers and explosives to methodically destroy house after house. They paid special attention to historical monuments, Polish national archives and places of interest.[140]

By January 1945 85% of the buildings were destroyed: 25% as a result of the Uprising, 35% as a result of systematic German actions after the uprising, and the rest as a result of the earlier Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and the September 1939 campaign.[8] Material losses are estimated at 10,455 buildings, 923 historical buildings (94%), 25 churches, 14 libraries including the National Library, 81 primary schools, 64 high schools, University of Warsaw and Warsaw University of Technology, and most of the historical monuments.[8] Almost a million inhabitants lost all of their possessions.[8] The exact amount of losses of private and public property as well as pieces of art, monuments of science and culture is unknown but considered enormous. Studies done in the late 1940s estimated total damage at about $30 billion US dollars.[141] In 2004, President of Warsaw Lech Kaczyński, later President of Poland, established a historical commission to estimate material losses that were inflicted upon the city by German authorities. The commission estimated the losses as at least US$31.5 billion at 2004 values.[142] Those estimates were later raised to US$45 billion 2004 US dollars and in 2005, to $54.6 billion.[143]

Casualties

The exact number of casualties on both sides is unknown. Estimates of casualties fall into roughly similar ranges. Polish civilian deaths are estimated at between 150,000 and 200,000.[9] Both Polish and German military personnel losses are estimated separately at under 20,000.[8][144]

| Side | Civilians | KIA | WIA | MIA | POW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | 150,000-200,000[9] | 15,200[8] 16,000[144] 16,200[145] |

5,000[8] 6,000[146] 25,000[9] |

all declared dead[144] | 15,000[8][144] |

| German[147] | unknown | 2,000 to 3,000 killed,[8] or 16,000 killed and missing[8] | 9,000[8][144] | 7,000[144][148] | 2,000[8] to 5,000[144] |

In addition, Germans lost some valuable military equipment, including 3 aircraft, 310 tanks and armored cars, 340 trucks and cars and 22 light (75 mm) artillery pieces.[8]

After the war

"I would like to protest against mean and cowardly attitude of the British press towards the uprising in Warsaw [...]. In general an impression was created, that the Poles deserve to be beaten, even though they were doing exactly all of this, to which allies broadcasting stations were calling them for several years […]. This is my message for leftist journalists and for intelligence – in general. Remember, that one always pays for his dishonesty and cowardice. Don’t even think, that for years on end you will be shoes licking servants of the Soviet regime, and then suddenly you will return to the spiritual decency." - George Orwell, 1 September 1944[149]

Due in part to the lack of Soviet cooperation the Warsaw Uprising and Operation Tempest failed in their primary goal: to free part of the Polish territories so that a government loyal to the Polish government-in-exile could be established there instead of a Soviet backed government. There is no consensus among historians as to whether that was ever possible, or whether those operations had any other lasting effect.

Most soldiers of the Home Army (including those who took part in the Warsaw Uprising) were persecuted after the war: captured by the NKVD or UB political police. They were interrogated and imprisoned on various charges like for example - "fascism".[150][151] Many of them were sent to Gulags, executed or "disappeared".[150] Between 1944 and 1956, all of the former members of Batalion Zośka were incarcerated in Soviet prisons.[152] Many insurgents, captured by the Germans and sent to POW camps in Germany, were later liberated by British, American and Polish forces and remained in the West. Among those were the leaders of the uprising: Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski and Antoni Chruściel.

The facts of the Warsaw Uprising were inconvenient to Stalin, and were twisted by propaganda of the People's Republic of Poland, which stressed the failings of the Home Army and the Polish government-in-exile, and forbade all criticism of the Red Army or the political goals of Soviet strategy.[153] In the immediate post-war period, the very name of the Home Army was censored, and most films and novels covering the 1944 Uprising were either banned or modified so that the name of the Home Army did not appear.[153] From the 1950s on, Polish propaganda depicted the soldiers of the Uprising as brave, but the officers as treacherous, reactionary and characterized by disregard of the losses.[153][154] The first publications on the topic taken seriously in the West were not issued until the late 1980s. In Warsaw no monument to the Home Army was built until 1989. Instead, efforts of the Soviet-backed People's Army were glorified and exaggerated.

By contrast, in the West the story of the Polish fight for Warsaw was told as a tale of valiant heroes fighting against a cruel and ruthless enemy. It was suggested that Stalin benefited from Soviet non-involvement, as opposition to eventual Russian control of Poland was effectively eliminated when the Nazis destroyed the partisans.[155] The belief that the Uprising failed because of deliberate procrastination by the Soviet Union contributed to anti-Soviet sentiment in Poland. Memories of the Uprising helped to inspire the Polish labour movement Solidarity, which led a peaceful opposition movement against the Communist government during the 1980s.[156]

Until the 1990s, historical analysis of the events remained superficial because of official censorship and academic disinterest.[157] Research into the Warsaw Uprising was boosted by the fall of communism in 1989, due to the abolition of censorship and increased access to state archives. As of 2004, however, access to some material in British, Polish and ex-Soviet archives was still restricted.[158] Further complicating the matter is the British claim that the records of the Polish government-in-exile were destroyed,[159] and material not transferred to British authorities after the war was burnt by the Poles in London in July 1945.[160][161]

In Poland, 1 August is now a celebrated anniversary. On 1 August 1994, Poland held a ceremony commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Uprising to which both the German and Russian presidents were invited.[10] Though the German President Roman Herzog attended, the Russian President Boris Yeltsin declined the invitation; other notable guests included the U.S. Vice President Al Gore.[10][162] Herzog, on behalf of Germany, was the first German statesman to apologize for German atrocities committed against the Polish nation during the Uprising.[162] During the 60th anniversary of the Uprising in 2004, official delegations included: German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, UK deputy Prime Minister John Prescott and US Secretary of State Colin Powell; Pope John Paul II send a letter to the president of Warsaw, Lech Kaczyński on this occasion.[163] Russia once again did not send a representative.[163] A day before, 31 July 2004, the Warsaw Uprising Museum opened in Warsaw.[163]

Photograph gallery

German guards next to a guardhouse and a bunker at the Puławska Street gate to the base of air defence units (Flakkaserne) located at the old Polish base between Puławska and Rakowiecka Streets.) July 1944 |

German guards next to a guardhouse and a bunker at the Puławska Street gate to the base of air defence units (Flakkaserne) located at the old Polish base between Puławska and Rakowiecka Streets.) July 1944 |

Aleje Szucha street with German bunker on the right side of the street viewed from Unii Lubelskiej Square. Behind the barriers lies German district sometimes called “German Ghetto”. July 1944 |

Aleje Szucha street with German bunker on the right side of the street viewed from Unii Lubelskiej Square. Behind the barriers lies German district sometimes called “German Ghetto”. July 1944 |

Guardhouse and a bunker at the gate to the Stauferkaserne base at Rakowiecka 4 Street housing an SS battalion. View from Rakowiecka street corner with Kazimierzowska street. July 1944 |

Month before Warsaw Uprising: Guardhouse and a bunker in front of City Headquarters building at 4 Piłsudski Square in the back townhouses along of Krakowskie Przedmieście street, from the left: 40 (fragment), 38 and 36 (ruins). July 1944 |

Bunker and gate of Abschnittwache Nord (so called Nordwache) building at Żelazna 75a street behind barbed wire obstacles “Cheval de fries” July 1944 |

German bunker on Kierbiedź Bridge.July 1944 |

German bunker in front of National Museum in Aleje Jerozolimskie. July 1944 |

Bunker in front of gate to University of Warsaw converted to a base for Wehrmacht viewed from Krakowskie Przedmieście Street. July 1944 |

Insurgents from "Chrobry I" Battalion in front of German police station “Nordwache” at the junction of Chłodna and Żelazna Streets. 3 August 1944 |

Insurgents from Ruczaj Battalion after fight for Mała PASTa building take pictures at the main entrance at Piusa 19 Street next to a bunker. 24 August 1944 |

Members of the SS-Sonderregiment Dirlewanger in Warsaw in window of townhouse at Focha 9 Street. In the glass reflection one can see details of the townhouse on the oposite side of the street at Focha 8 Street August 1944 |

SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth "Butcher of Wola" (left, in Cossack headgear) and the Regiment III of Cossacks of Jakub Bondarenko during Warsaw Uprising around Wolska street. Third Regiment of Cossacks contained a mix of Cossacks from many regions, and Jakub Bondarenko was commanding 5th Regiment of Kuban Cossack Infantry |

One of the German POW's from PAST-a building at Zielna 37 street, was SS-Sturmscharführer, who supposedly was terrorizing other defenders 20 August 1944 |

German soldier killed by insurgents during attack on Mała PASTa. 23 August 1944 |

Barricade erected such on Napoleon Square. In background: captured Hetzer tank destroyer. 3 August 1944 |

Popular culture

Lao Che - Powstanie Warszawskie (an album of Polish band wholly dedicated to the uprising)

Sabaton - Uprising (Swedish Power/Heavy metal band Sabaton wrote a song about this event)

See also

- Kanał (film)

- Krakow Uprising (1944)

- Krzyż Powstania Warszawskiego

- Ochota massacre

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Powstanie Warszawskie (album)

- Anglo-Polish Radio ORLA.fm

Notes and references

- ↑ Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44. The Battle for Warsaw. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0330488635.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44. The Battle for Warsaw. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0330488635.

- ↑ Neil Orpen (1984). Airlift to Warsaw. The Rising of 1944. University of Oklahoma. ISBN 8324702350.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Borodziej, Włodzimierz (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Translated by Barbara Harshav. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299207304 p. 74.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Borowiec, Andrew (2001). Destroy Warsaw! Hitler's punishment, Stalin's revenge. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0275970051. p. 6.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 75.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Comparison of Forces, Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 "FAQ". Warsaw Uprising. http://www.warsawuprising.com/faq.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Borowiec, p. 179.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Stanley Blejwas, A Heroic Uprising in Poland , 2004

- ↑ Frank's diary quoted in Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44. The Battle for Warsaw. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0330488635. p. 367.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 204–206.

- ↑ sojusznik naszych sojuszników: Instytut Zachodni, Przegląd zachodni, v.47 no.3-4 1991

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 The Warsaw Rising, polandinexile.com

- ↑ Davies, pp. 48, 115.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 206–208.

- ↑ The NKVD Against the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), Warsaw Uprising, based on Andrzej Paczkowski. Poland, the "Enemy Nation", pp. 372-375, in Black Book of Communism. Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press, London, 1999.

- ↑ Davies, p. 209.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 4 and Davies, p. 213.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Part 1 – "Introduction"". Poloniatoday.com. http://www.poloniatoday.com/uprising1.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Warsaw Rising Museum: Before the Rising

- ↑ Davies, p. 117.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 5.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 4 and Davies, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ "The Tragedy of Warsaw and its Documentation", By The Duchess of Atholl,. D.B.E., Hon. D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.C.M. 1945, London

- ↑ 27.00 27.01 27.02 27.03 27.04 27.05 27.06 27.07 27.08 27.09 27.10 David M. Glantz (2001). The Soviet-German War 1941–1945: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay Retrieved on 20 February 2009

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Pomian, Andrzej. The Warsaw Rising: A Selection of Documents. London, 1945

- ↑ full text of broadcast

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 69,70. ISBN 9780299207304. http://books.google.com/?id=YHO0F65ifDIC&pg=PA69&dq=jan+nowak+uprising+july+29.

- ↑ Davies, p. 232.

- ↑ Arnold-Forster, Mark (1973; repr. 1983). The World at War. London: Collins/Thames Television repr. Thames Methuen. ISBN 0423006800. p. 178.

- ↑ Borkiewicz, p. 31.

- ↑ Chodakiewicz, Marek (April 2002). "Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944". The Sarmatian Review Issue 02/2002 pp.875–880.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 70.

- ↑ The exact number of Poles of Jewish ancestry and Jews to take part in the uprising is a matter of controversy. General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski estimated the number of Jewish Poles in Polish ranks at 1,000, other authors place it at between several hundred and 2,000. See for example: (Polish) Edward Kossoy. Żydzi w Powstaniu Warszawskim. Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 (Polish) Stowarzyszenie Pamięci Powstania Warszawskiego 1944, Struktura oddziałów Armii Krajowej

- ↑ All figures estimated by Aleksander Gieysztor and quoted in (Polish) Bartoszewski, Władysław T. (1984). Dni Wałczacej Stolicy: kronika Powstania Warszawskiego. Warsaw: Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego; Świat Książki. pp. 307–309. ISBN 9788373916791.

- ↑ NW36. "Other Polish Vehicles". Mailer.fsu.edu. http://mailer.fsu.edu/~akirk/tanks/pol/OtherPolish.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ "Polish Armored Fighting Vehicles of the Warsaw Uprising 1 August to 2 October 1944". Achtung Panzer!. http://www.achtungpanzer.com/pol/polot_2.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ "Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Part 6 – "Warsaw Aflame"". Poloniatoday.com. http://www.poloniatoday.com/uprising6.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Mariusz Skotnicki, Miotacz ognia wzór "K", in: Nowa Technika Wojskowa 7/98, p.59. ISSN 1230-1655

- ↑ "Improvised Armored Car "Kubus"". Achtung Panzer!. http://www.achtungpanzer.com/pol/kubus.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ (Polish) Adam Borkiewicz (1957). Powstanie Warszawskie 1944. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo PAX. p. 40.

- ↑ Borkiewicz, p. 41.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 93.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 94.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 666–667.

- ↑ 49.00 49.01 49.02 49.03 49.04 49.05 49.06 49.07 49.08 49.09 49.10 49.11 49.12 49.13 49.14 49.15 "Timeline". Warsaw Uprising. http://www.warsawuprising.com/timeline.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 79 and Davies, p. 245.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 80.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 95–97.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 86–87 and Davies, p. 248.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 245–247.

- ↑ (Polish) Bartelski, Lesław M. (2000). Praga. Warsaw: Fundacja "Wystawa Warszawa Wałczy 1939–1945". p. 182. ISBN 8387545333.

- ↑ (Polish) (German) various authors; Czesław Madajczyk (1999). "Nie rozwiązane problemy powstania warszawskiego". In Stanisława Lewandowska, Bernd Martin. Powstanie Warszawskie 1944. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Polsko-Niemieckie. p. 613. ISBN 8386653086.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 89.

- ↑ Davies, p. 252.

- ↑ (Polish) "Muzeum Powstania otwarte". BBC Polish edition. 2004-10-02. http://www.bbc.co.uk/polish/domestic/story/2004/10/041002_uprising_warsaw_museum.shtml.

- ↑ (Polish) Jerzy Kłoczowski (1998-08-01). "O Powstaniu Warszawskim opowiada prof. Jerzy Kłoczowski". Gazeta Wyborcza. http://miasta.gazeta.pl/warszawa/1,54182,1601810.html.

- ↑ "Warsaw Uprising of 1944: PART 5 - "THEY ARE BURNING WARSAW"". Poloniatoday.com. 1944-08-05. http://www.poloniatoday.com/uprising5.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ "The Rape of Warsaw". Stosstruppen39-45.tripod.com. http://stosstruppen39-45.tripod.com/id6.html. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Steven J. Zaloga, Richard Hook, The Polish Army 1939-45, Osprey Publishing, 1982, ISBN 0850454174, Google Print, p.25

- ↑ The slaughter in Wola at Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ Davies, pp. 254–257.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 112.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Krystyna Wituska, Irene Tomaszewski, Inside a Gestapo Prison: The Letters of Krystyna Wituska, 1942–1944, Wayne State University Press, 2006, ISBN 0814332943,Google Print, p.xxii

- ↑ Davies, p. 282.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 333, 355.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 132–133 and Davies, p. 354.

- ↑ Davies, p. 355.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp.138–141 and Davies, p. 332.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 358–359.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 75.4 For description of Berling's landings, see Warsaw Uprising Timeline, Warsaw Uprising Part 10 – "The Final Agony", and p.27 of Steven J. Zaloga's The Polish Army, 1939–45 (Google Print's excerpt)

- ↑ Richard J. Kozicki, Piotr Wróbel (eds), Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945, Greenwood Press, 1996, ISBN 0313260079, Google Print, p.34

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 120 and Bell, J (2006). Besieged. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1412805864 p. 196.

- ↑ (Polish) Nawrocka-Dońska, Barbara (1961). Powszedni dzień dramatu (1 ed.). Warsaw: Czytelnik. p. 169.

- ↑ (Polish) Tomczyk, Damian (1982). Młodociani uczestnicy powstania warszawskiego. Łambinowice: Muzeum Martyrologii i Walki Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach. p. 70.

- ↑ (Polish) Ryszard Mączewski. "Stacja Filtrów". Architektura przedwojennej Warszawy. warszawa1939.pl. http://www.warszawa1939.pl/index.php?r1=koszykowa_filtry&r3=0. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 (Polish) various authors; Jadwiga Cieślakiewicz, Hanna Falkowska, Andrzej Paczkowski (1984). Polska prasa konspiracyjna (1939–1945) i Powstania Warszawskiego w zbiorach Biblioteki Narodowej. Warsaw: Biblioteka Narodowa. p. 205. ISBN 830000842X.

- ↑ (Polish) collection of documents (1974). Marian Marek Drozdowski, Maria Maniakówna, Tomasz Strzembosz, Władysław Bartoszewski. ed. Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim. Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ↑ (Polish) Zadrożny, Stanisław (1964). Tu--Warszawa; Dzieje radiostacji powstańczej "Błyskawica". London: Orbis. p. 112.

- ↑ Project InPosterum (corporate author). "Warsaw Uprising: Radio 'Lighting' (Błyskawica)". http://www.warsawuprising.com/paper/radio.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1982). Courier from Warsaw. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814317259.

- ↑ (Polish) Adam Nogaj. Radiostacja Błyskawica.

- ↑ Project InPosterum (corporate author) (2004). "John Ward". Warsaw Uprising 1944. http://www.warsawuprising.com/witness.htm#w9. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ↑ Davies, p. 450.

- ↑ Davies, p. 452.

- ↑ Davies, p. 453.

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 "American Radioworks on Warsaw Uprising". Americanradioworks.publicradio.org. http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/warsaw/c1.html. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 AIRDROPS FOR INSURGENTS at Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ Neil Orpen (1984). Airlift to Warsaw. The Rising of 1944. University of Oklahoma. p. 192. ISBN 8324702350.

- ↑ ALLIED AIRMEN OVER WARSAW at Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ Kamil Tchorek, Escaped British Airman Was Hero of Warsaw Uprising

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Stalin's Private Airfields, Warsaw Rising Museum

- ↑ Warsaw Uprising CNN Special – 26 August. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 121 and Davies, p. 377.

- ↑ Davies, p. 377.

- ↑ Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces September 1944: 17,18,19 copied from USAF History Publications & wwii combat chronology (pdf))

- ↑ Davies, p. 392.

- ↑ Davies, p. 391.

- ↑ Davies, p. 381.

- ↑ Borowiec, p. 150.

- ↑ Davies, p. 304.

- ↑ SS: The Waffen-SS War in Russia 1941–45 Relevant page viewable via Google book search

- ↑ Borowiec, pp. 148–151.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 (Polish) Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (1993-07-31). "Białe plamy wokół Powstania". Gazeta Wyborcza (177): 13. http://szukaj.gazeta.pl/archiwum/1,0,130276.html?kdl=19930731GW&wyr=Nowak-Jeziora%25F1ski%2B. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ↑ According to Polish documents, Mikołajczyk informed the Soviet foreign minister Molotov at 9:00 p.m. on 31 July (Ciechanowski (1974), p.68)

- ↑ The Soviet Conduct of Tactical Maneuver: Spearhead of the Offensive by David M Glantz. Map of the front lines on 3 August 1944 - Google Print, p.175

- ↑ The Soviet Conduct of Tactical Maneuver: Spearhead of the Offensive by David M Glantz, Google Print, p.173

- ↑ Map of 2nd Tank Army operations map

- ↑ Official statement of Mikołajczyk quoted in Borowiec, p. 108.

- ↑ Davies, p. 444.

- ↑ Davies, p. 283.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 (Polish) Bartoszewski, Władysław T. (1984). Dni Walczącej Stolicy: kronika Powstania Warszawskiego. Warsaw: Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego; Świat Książki. ISBN 9788373916791.

- ↑ Davies, p. 320.

- ↑ Davies, p. 417.

- ↑ Davies, p. 418.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 440–441.

- ↑ e.g. Davies, pp. 154–155, 388–389.

- ↑ Davies, p. 422.

- ↑ Davies, p. 330.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 332–334.

- ↑ Davies, p. 353.

- ↑ Davies, p. 358.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 125 and Borowiec, p. 165.

- ↑ Davies, p. 400.

- ↑ Borodziej, p. 126 and Borowiec, p. 169.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 408–409.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 409–411.

- ↑ The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov (London, 1971) pp.551–552, quoted in Davies, pp. 420–421.

- ↑ Davies, p. 427.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 (Polish) Zaborski, Zdzisław (2004). Tędy przeszła Warszawa: Epilog powstania warszawskiego: Pruszków Durchgangslager 121, 6 VIII - 10 X 1944. Warsaw: Askon. p. 55. ISBN 8387545864.

- ↑ Niels Gutschow, Barbarta Klain: Vernichtung und Utopie. Stadtplanung Warschau 1939–1945, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-88506-223-2

- ↑ Peter K. Gessner, "For over two months..."

- ↑ Anthony M. Tung, Preserving the World's Great Cities: The Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis, Three Rivers Press, New York, 2001, ISBN 0517701480. See Chapter Four: Warsaw: The Heritage of War (online excerpt).

- ↑ Vanessa Gera Warsaw bloodbath still stirs emotions, Chicago Sun-Times, 1 August 2004

- ↑ (Polish) "Warszawa szacuje straty wojenne" (in Polish). http://um.warszawa.pl/v_syrenka/new/index.php?dzial=aktualnosci&strona=aktualnosci_archiwum&poczatek=2004-02&ak_id=171&kat=2. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ See the following pages on the official site of Warsaw: Raport o stratach wojennych Warszawy LISTOPAD 2004, Straty Warszawy w albumie and Straty wojenne Warszawy

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 144.2 144.3 144.4 144.5 144.6 (Polish) Jerzy Kirchmayer (1978). Powstanie warszawskie. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 576. ISBN 830511080X.

- ↑ (Polish) Inst. Historyczny im. Gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie (1950). Polskie siły zbrojne w drugiej wojnie światowej. III. London: Inst. Historyczny im. Gen. Sikorskiego. p. 819.

- ↑ Kirchmayer, p. 460.

- ↑ The number includes all troops fighting under German command, including Germans, Azeri, Hungarians, Russians, Ukrainians, Cossacks, etc.

- ↑ German MIA were never declared dead and are still considered missing 60 years after the battle. According to various Polish historians (among them Col. Jerzy Kirchmayer) the purpose of this policy is to lessen the total casualty rate.

- ↑ Orwell in Tribune: ‘As I Please’ and Other Writings 1943-7 by George Orwell (Compiled and edited by Paul Anderson) Politicos, 2006

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 Andrzej Paczkowski. Poland, the "Enemy Nation", pp. 372–375, in Black Book of Communism. Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press, London. See online excerpt.

- ↑ Michał Zając, Warsaw Uprising: 5 pm, 1 August 1944, Retrieved on 4 July 2007.

- ↑ Żołnierze Batalionu Armii Krajowej "Zośka" represjonowani w latach 1944-1956 ", Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Warszawa 2008, ISBN 978-83-60464-92-2

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 153.2 (Polish) Sawicki, Jacek Zygmunt (2005). Bitwa o prawdę: Historia zmagań o pamięć Powstania Warszawskiego 1944-1989. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo "DiG". p. 230. ISBN 837181366X.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 521–522.

- ↑ Arnold-Forster, Mark (1973; repr. 1983). The World at War. London: Collins/Thames Television repr. Thames Methuen. ISBN 0423006800. pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Davies, pp. 601–602.

- ↑ Davies, p. ix.

- ↑ Davies, p. xi.

- ↑ Davies, p. 528.

- ↑ Peszke, Michael Alfred (October 2006). "An Introduction to English-Language Literature on the Polish Armed Forces in World War II". The Journal of Military History 70: 1029–1064.

- ↑ See also: Tessa Stirling, Daria Nalecz, and Tadeusz Dubicki, eds. (2005). Intelligence Co-operation between Poland and Great Britain during World War II. Vol. 1: The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee. London and Portland, Oregon: Vallentine Mitchell. Foreword by Tony Blair and Marek Belka. ISBN 085303656X

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Władysław Bartoszewski interviewed by Marcin Mierzejewski, On the Front Lines, Warsaw Voice, 1 September 2004

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 163.2 60TH ANNIVERSARY, Warsaw Rising Museum

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mnxvdz65y8s&feature=related

Further reading

-

- See also http://www.polishresistance-ak.org/FurtherR.htm for more English language books on the topic.

- (Polish) Bartoszewski, Władysław T. (1984). Dni Walczącej Stolicy: kronika Powstania Warszawskiego. Warsaw: Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego; Świat Książki. ISBN 9788373916791.

- (Polish) Borkiewicz, Adam (1957). Powstanie warszawskie 1944: zarys działań natury wojskowej. Warsaw: PAX.

- (Polish) Ciechanowski, Jan M. (1987). Powstanie warszawskie: zarys podłoża politycznego i dyplomatycznego. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. ISBN 830601135X.

- (Polish) Kirchmayer, Jerzy (1978). Powstanie warszawskie. Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 830511080X.

- (Polish) Przygoński, Antoni (1980). Powstanie warszawskie w sierpniu 1944 r.. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. ISBN 830100293X.

- Borodziej, Włodzimierz (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Translated by Barbara Harshav. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299207304.

- Borowiec, Andrew (2001). Destroy Warsaw! Hitler's punishment, Stalin's revenge. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0275970051.

- Ciechanowski, Jan M. (1974). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521202035.

- Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44. The Battle for Warsaw (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Viking. ISBN 9780670032846.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Warsaw 1944; Poland's big for freedom Osprey Campaign Series #205. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978184033520.